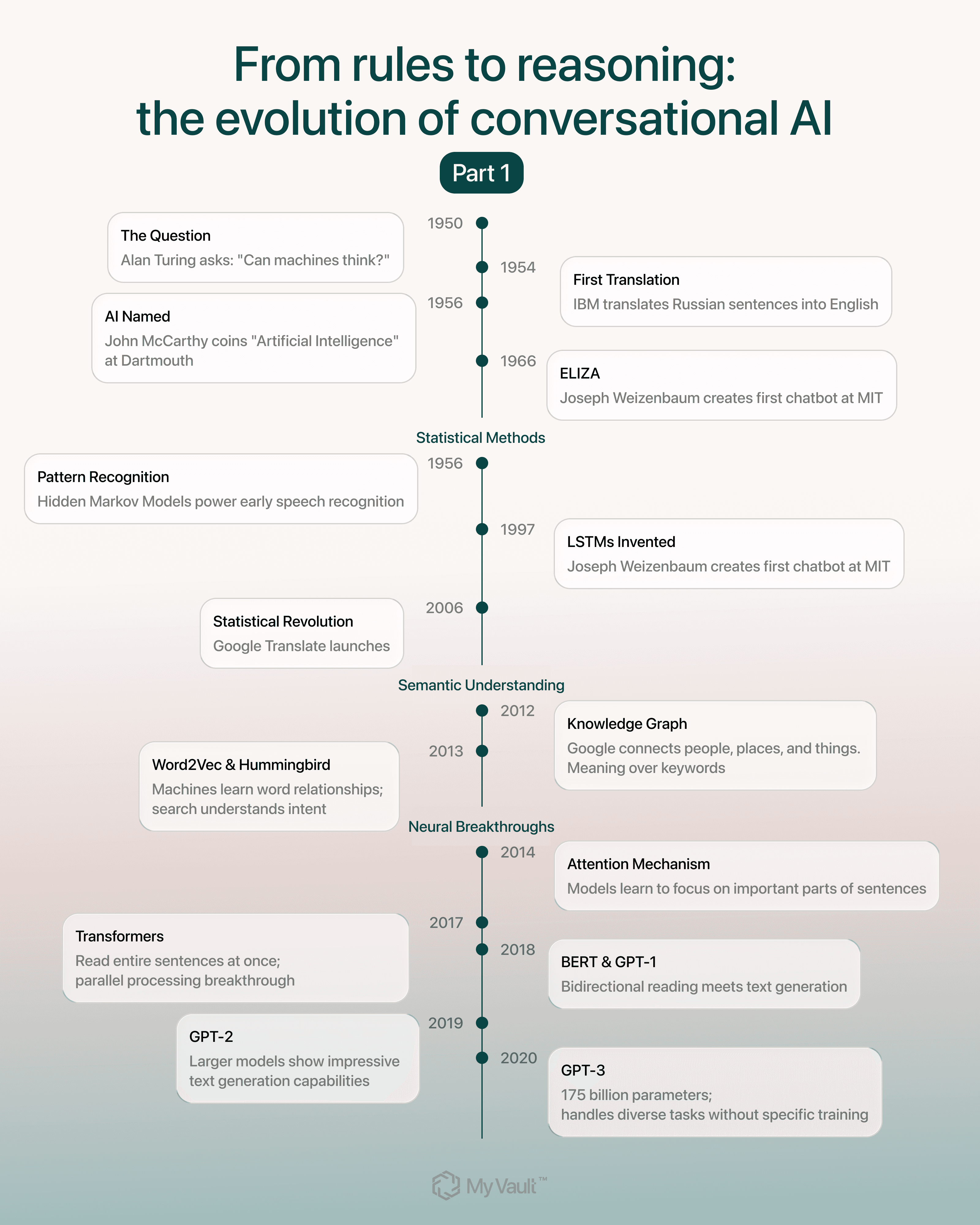

From rules to reasoning: the evolution of conversational AI (Part 1)

In 1950, Alan Turing asked a question that would define computer science for over seventy years: Can machines think?

How the question even started

Turing was writing at the moment when the first general purpose computers had just been built. “I have no very convincing arguments of a positive nature to support my views”, he wrote.

Instead of arguing for machines, he turned his attention to those who doubted them. He went after religious objections, philosophical objections, and questions about consciousness. He showed that no one could prove machines couldn’t think.

Turing predicted that by the year 2000, a computer could imitate a human well enough that an average judge would guess correctly less than 70% of the time after a five minute conversation. He was wrong about when and how it would happen, but he was right about one thing. Once machines could process language well enough to mimic understanding, everything would change.

Six years later, in 1956, John McCarthy gave Turing’s idea a name. He called it artificial intelligence (AI) at the Dartmouth Summer Research Project. McCarthy believed machines could simulate human thinking if we found the right approach. From that point on, it became a field of study.

The ELIZA effect: Why early chatbots talked a lot but understood nothing

People didn’t just want computers to talk. They wanted them to actually help.

If you’ve ever searched through emails or documents and found nothing useful, you already know why this was important.

Before chatbots, researchers were already trying to make computers handle language. In 1954, IBM translated Russian sentences into English using one of the first rule-based systems.

Then, in 1966, MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum created ELIZA, the first chatbot. It mimicked a therapist using the Rogerian method, turning your own words into questions to keep the conversation going. But the program was limited by its scripts.

ELIZA didn't understand language at all. It only recognized a few words and swapped them into prewritten responses. You'd type "I am sad" and ELIZA would respond "How long have you been sad?" It looked intelligent, but it was just an imitation.

Even though users knew ELIZA didn't understand a single word, some still grew emotionally attached. That reaction later became known as the ELIZA effect, the human tendency to project understanding and emotion onto a system that is only following patterns.

A conversation with ELIZA. Source: Flickr

For a long time this was how people used computers. You had to adjust to the system, with the exact commands and specific keywords. One typo, one wrong word, and the computer couldn't help you.

Computers finally started learning from real language

By the 1980s and 1990s, researchers started seeing the limits of rule-based systems. Language was too unpredictable for fixed instructions to handle, so rules stayed, but data and probability began taking over.

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), which estimate the most likely next word based on real speech data, powered early speech recognition. Annotated datasets like the Penn Treebank, basically large collections of labeled sentences, helped machines learn patterns directly from human text.

Instead of writing instructions, they gave computers massive amounts of text to analyze. If certain words appeared near each other often, the system treated them as related.

Give a machine enough language, and it starts to notice patterns. “Expired” appears near “insurance policy.” “Premium” appears near “payment.” “Claim” appears near “denied.” No one programmed these connections. The system learned associations on their own.

It was an early sign of what would eventually become natural language processing (NLP).

But spotting patterns isn’t the same as understanding them. To get past simple connections, computers needed to learn from a lot of real text and decide which associations were truly important. That’s why the field moved toward statistical methods.

Machines learned from examples instead of rules

In the 2000s, tools like Google Translate changed direction. Instead of following instructions written by engineers, they started learning from millions of real examples. If a certain phrase in English often matched a certain phrase in French, the system learned to pair them. For the first time, computers could pick up hints of meaning from patterns in massive amounts of text.

It wasn’t understanding, but it was a step toward it.

Neural networks tried to follow longer thoughts

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, researchers developed neural networks that could remember context across longer sequences.

Architectures like LSTMs, created in 1997 but not widely used until the 2010s, helped machines maintain conversation context and translate between languages more naturally. But they still processed text sequentially, word by word, which limited their ability to understand how distant words in a sentence related to each other

Search engines still needed exact words

While neural networks were improving, search engines were stuck in an older world.

Between 1998 and 2011, Google depended on exact keywords and PageRank, a system that ranked pages based on incoming links, not on the meaning of the content. To rank for “running shoes,” you had to use that exact phrase. “Athletic footwear” or “sneakers for jogging” wouldn’t appear.

Typos broke results. Special characters like ö or ñ would confuse the system. The machine was reading word by word, character by character, with no sense of meaning.

At the same time, research outside search engines was focused on helping machines follow longer thoughts and remember what came earlier in the sentence.

Search engines stopped acting like robots

In 2012, Google introduced the Knowledge Graph, which connected people, places, and things into a network of meaning. One year later, in 2013, it followed with the Hummingbird update, which helped search engines interpret what people meant instead of only what they typed.

Around the same time, Word2Vec learned relationships between words by scanning billions of real sentences and grouping words that appeared in similar contexts. Suddenly you didn’t need perfect wording. The system finally understood what you meant.

Models learned to read context instead of matching words

In 2014, researchers created the attention mechanism, a way for models to focus on the most important parts of a sentence instead of treating every word the same.

In 2017, researchers built on that idea and developed transformers. For the first time, models could analyze entire sentences at once and map how every word connects. It made language processing faster, more accurate, and easier to scale.

In 2018, Google launched BERT, a model that changed how machines read language. Instead of looking at words one by one, BERT reads them in both directions at the same time, modeling how each word fits into the whole sentence.

A search like "British traveler to USA needs a visa" would finally return results for UK citizens entering the US, not the other way around. The system could finally map the relationship between the words, not just see them as a list.

The same year, OpenAI built GPT-1, a small test model trained on books. GPT-2 arrived in 2019 with much more data and produced text that sounded natural. GPT-3 followed in 2020 with 175 billion parameters. It could write essays, code, arguments, and short stories with a level of fluency that surprised even experts. But it stayed behind an API, so most people never used it directly.

These models showed the approach was strong enough to support the next generation.

LLMs became conversational partners

In 2022, large language models (LLMs) moved from research labs into everyday use.

Search got better. Assistants became less frustrating. And the documents, messages, and files in your digital life finally seemed easier to navigate. At least they were supposed to. Anyone who has lost an important file at the worst possible moment knows how fragile that promise is.

When ChatGPT came out in late 2022, built on GPT 3.5, people tried it immediately. It hit one million users in five days and reached one hundred million in two months, becoming the fastest growing consumer app in history. It showed that people wanted AI that could respond in a way that felt natural and context aware, even though the model was still predicting patterns rather than understanding them.

Now the AI recognizes that “that’s sick” is used as a compliment, not an insult. It can map “I’m feeling blue” to sadness. Ask “Why did the chicken cross the road?” and it can recognize that you want a joke, not a literal explanation. It came from training on massive, diverse language that showed the model how people use words in context.

Language AI in everyday life

By 2025, natural language processing is the foundation of how machines communicate with people. Voice assistants, recommendation engines, content filters, medical tools, code generators, and self-driving systems all depend on progress that started with recognizing simple word patterns.

Modern systems can track context across documents, hold parts of conversations in memory, and respond clearly and accurately.

What all this progress leads to

It’s taken seventy years to get from Turing’s question to today’s AI. Better language technology changed how people search, work, and handle information.

People now want tools that can respond to what they ask for, but they don’t want to give companies full access to everything they store. That’s a reasonable concern, especially when important documents and personal data are involved.

The good news is that modern language models don’t need to see your files to help you find them. They can answer your questions while your documents stay encrypted and private.

At MyVault, we use this approach because it keeps control in your hands. If you want an assistant that can help with your documents without needing to see them, you can join our private launch.

Stay tuned for Part 2, where we’ll explore the next phase of the story about how these foundations evolved into the LLM era we’re living in now.

Related posts

Feb 3, 2026

Household systems that pay for themselves in hours

Mental load means remembering when car insurance renews, tracking which child needs new shoes, knowing the fridge filter expires next month. Every household runs on hundreds of small details that someone must hold in memory.

Sead Fadilpasic

Jan 27, 2026

The Habsburg effect: why your data just got more valuable

The European Habsburgs built an empire through strategic marriages, consolidating power by keeping bloodlines strictly within the family. Something similar is happening with AI right now.

Markos Symeonides

Jan 21, 2026

The superuser problem: why AI agents are 2026's “biggest insider threat”

The primary security issue with AI agents is their access.

Markos Symeonides